If anyone was interested in surveilling my daily habits, they might surmise that I live in New York. I subscribe to the New York Times and The New Yorker. I get my day started with the “Brian Lehrer Show” on WNYC and usually drink my coffee out of a mug with the radio host’s name. And if there is time, I segue into “All Of It” with Alison Stewart before turning the tuner to my local NPR station, KQED.

(Don’t get it twisted, I am a die-hard Golden State Warriors fan and have joined the Valkyries bandwagon, but it is hard not to root for the Knicks when they’re not playing the Dubs.)

I live in the San Francisco Bay Area and haven’t had an address in New York since 1987. But even before I moved there in the early 80s I felt the city’s pull. It was a place both of my parents loved. My mother, a native of Newark, New Jersey, shared fond memories of day trips into Manhattan. My father had spent his young adulthood and the bulk of his career as a journalist in Harlem. In my mind, New York has always been a place of wonder.

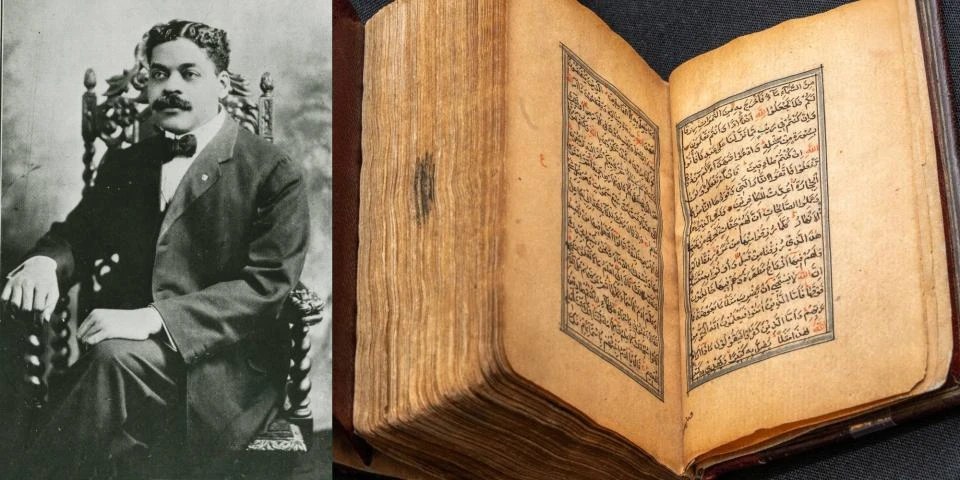

So, it would be no surprise to anyone that my first act on New Year’s Day was to tune in to the Inauguration festivities for New York Mayor Zohran Mamdani. In line with his Muslim faith, Mamdani swore to uphold the constitution by placing his hand on the Qur’an. Two of the holy books selected for the occasion belonged to his grandparents. The other was from the collection of Arturo Schomburg.

Schomburg was a Black historian born in Puerto Rico. According to Wikipedia, his mother was a freeborn Black woman from St. Croix; his father was of German descent. As a young student, Schomburg recalled an elementary school teacher declaring that Black people had no history. Schomburg, who identified as “Afroborinqueño” or Afro-Puerto Rican, devoted his life to dispelling that lie by documenting the history of the African diaspora.

Schomburg studied commercial printing at San Juan Puerto Rico’s Instituto Popular, and he studied Negro literature at St. Thomas College on the island of St. Thomas. (St. Thomas and St. Croix, where his mother was born, were occupied by the Danish until they were sold, along with St. John, to the United States in 1917.)

At the age of 17, he settled in New York, where his day jobs included teaching Spanish, working as a messenger and clerk for a law firm and eventually supervising the Caribbean and Latin Mail Sections of Bankers Trust. In the meantime, he pursued his passion of doggedly collecting and curating evidence of a rich Black culture and intellectual life from Africa and across the world. He co-founded the Negro Society for Historical Research and was a significant figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

Schomburg sold his collection of art, literature, and historical artifacts to the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library. That collection would become the basis of what is now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which currently is celebrating its 100th anniversary.

That center is where I discovered the writings of my father, which inspired this website. And I was jazzed when I read that one of the Qur’ans featured in Mamdani’s swearing-in had been loaned to him by the Schomburg.

“The Schomburg Center is honored to have an object from its holdings included in this historic moment for New York City,” Joy Bivins, the Center’s director, said in a Dec. 31 press release.

“As we celebrate 100 years of collecting, preserving, and sharing the riches of global Black culture at this singular institution, we are delighted that Mayor-elect Mamdani selected a Qur’an from our namesake’s personal collection to mark the beginning of his administration.”

“This marks a significant moment in our city’s history, and we are deeply honored that Mayor Mamdani chose to take the oath of office using one of the Library’s Qur’ans,” added Anthony W. Marx, president and CEO of The New York Public Library. “This specific Qur’an, which Arturo Schomburg preserved for the knowledge and enjoyment of all New Yorkers, symbolizes a greater story of inclusion, representation, and civic-mindedness.”

At a time when the current occupant of the White House has launched a campaign of historical erasure, it is encouraging to see the Schomburg in the spotlight.