Last Monday, when I found myself having trouble getting out of bed, I just assumed it was the winter pall, or maybe the martinis I had consumed over the President’s Day weekend. But as much as I was inclined to, as Jamie Foxx sings, “blame it on the alcohol,” (By the way, did anyone see the Glee take on that song last week?) It was something more profound.

Last Monday, when I found myself having trouble getting out of bed, I just assumed it was the winter pall, or maybe the martinis I had consumed over the President’s Day weekend. But as much as I was inclined to, as Jamie Foxx sings, “blame it on the alcohol,” (By the way, did anyone see the Glee take on that song last week?) It was something more profound.

On Thursday, while I was visiting the local Family History Center searching for more pieces of the Ray family puzzle, I came upon my mother’s death record. Yep. Feb. 21, 2002. Nine years ago last Monday.

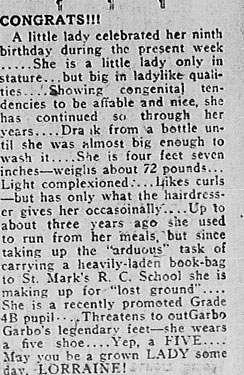

I thought about waiting until next year to pay tribute. It will be the 10th anniversary of her death, a milestone of sorts. But the future is not promised, as we all know, so I’m going to do it now. After all, there is no end to the gifts my mother poured into me. I’m sure I’ll have plenty to say next year.

I dug out an article I wrote for Essence in 1986 titled “How to get out of that rut and make life an adventure.” I used my mother as an example of someone who did that every day.

“My mother has always had a positive, energetic spirit and a sense of adventure unmatched in anyone else I’ve ever known,” I wrote in that Essence article. “A firm believer in going for the gusto, she ran track without the benefit of Wilma Rudolph as a role model. She was the first in her immediate family to earn a college degree. And while many of her peers were settling down with their own families, she was relocating to a strange city to take a new job. When she did marry and had my sisters and me, her world and her adventurous spirit simply grew. ‘There is no excuse for boredom,’ she’d say as she dragged us (and any other neighborhood child who happened to be within her reach) to dance classes, music lessons, museums, concerts, libraries and amusement parks — all on public transportation. And as my sisters and I came of age and began moving around to new jobs, new cities, new countries and new adventures, she was always there with her motherly caution, ‘Please be careful,’ and ‘Get some rest,’ — all the while saying ‘Go head, girl!'”

“My mother has always had a positive, energetic spirit and a sense of adventure unmatched in anyone else I’ve ever known,” I wrote in that Essence article. “A firm believer in going for the gusto, she ran track without the benefit of Wilma Rudolph as a role model. She was the first in her immediate family to earn a college degree. And while many of her peers were settling down with their own families, she was relocating to a strange city to take a new job. When she did marry and had my sisters and me, her world and her adventurous spirit simply grew. ‘There is no excuse for boredom,’ she’d say as she dragged us (and any other neighborhood child who happened to be within her reach) to dance classes, music lessons, museums, concerts, libraries and amusement parks — all on public transportation. And as my sisters and I came of age and began moving around to new jobs, new cities, new countries and new adventures, she was always there with her motherly caution, ‘Please be careful,’ and ‘Get some rest,’ — all the while saying ‘Go head, girl!'”

And I know she’s saying it now: To her daughter Malaya, who is still dancing, teaching and storytelling with a passion; To her granddaughter, M’Balia, who is about to get her degree all while working full time and raising three children and getting them through school and college. She’d say it to my daughter, Zuri, who is getting her acting on in London and will be an intern at the Cannes Film Festival in May. She’d say it to her granddaughter Kamaya, who has taken her big brother Jeremy, under her wing as he has determined to turn his life around. And, of course, she would say “well done” to her famous nephew Lamman, not just for his accomplishments as an actor, but for being a man with such a good, good heart.

My mom died on February 21, 2002 at 82. The weekend before, she had attended an AKA luncheon and the symphony. She was so active that when her friends didn’t hear from her in one 36-hour period, they knew something was up. They found her sitting in a comfy chair with her feet up, a cup of tea within reach.

She lived life fully to the end. That’s the best legacy she could leave.

The legacy of Mary Ray

26 Feb

The black press: A beacon of light in the racial darkness

6 FebIf you plan to be in Pittsburgh between Feb. 11 and Oct. 2, check out “America’s Best Weekly: A Century of the Pittsburgh Courier,” which will be on exhibit at the Heinz History Center. The Courier, where my father worked when I was a young girl in Pittsburgh, is celebrating 100 years of service to the black community. In its heyday, the Courier had 400 employees and its readership spanned the country. The Courier was a strong voice against segregation and particularly lynching. Pullman porters were enlisted to surreptitiously “drop” the papers along their Southern train routes.

“These papers were not welcomed in those states and oftentimes were confiscated and destroyed to keep African-Americans from reading newspapers,” Samuel Black, the exhibit’s curator, said in a recent interview with CBS Pittsburgh.

Robert Lavelle, an old family friend, who as a young man was responsible for coming up with those delivery routes, was interviewed for The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords, a film by award-winning filmmaker Stanley Nelson. Lavelle said that even though Pittsburgh was a relatively small city, the Courier had a name well beyond its borders “because it had tried to reach out to black people, no matter where they were, and we would try to send papers to those people. And as the people in those places became more numerous in terms of circulation, then those people would get a column in the Courier and maybe even on the front page of the Courier, and pretty soon that place had an edition of the Courier. So the Courier developed 13 editions and we would send papers to these various, regional places like the Midwest edition, the New England edition, the Chicago edition, the Philadelphia edition, and the Southern edition . . . We’d send them down by seaboard airline, Atlantic coastline railroad, down through Florida and all those places.”

On a personal note, my cousin Russell Williams recalls a visit his family made to Pittsburgh:

“Back in 1958, as my father finished his Ph.D. at Michigan State, we traveled back to South Carolina (where he taught at SC State), and we stopped in Pittsburgh to see Ebenezer and Mary Ray and their three daughters (Mary was my father’s favorite cousin). I remember Ebenezer taking us to the Pittsburgh Courier offices to show us how a newspaper was produced, and I carried home with me a souvenir (a piece of type) from that trip — a very interesting keepsake to my just-turned-seven-years-old

mind. Years later, I came to understand the important role that the Courier played nationally, and was very proud that I had a relative who had contributed to that impact.”

As I was four years old at the time and have no recollection of that visit, I was moved by Russell’s story.

Well before my father moved to Pittsburgh and joined the Courier, he tipped his hat to the Negro press as well. In 1935, the New York Age celebrated its 50th anniversary.

“For fifty years, The Age has lived; for fifty years it has been an articulate voice of the Negro race; for fifty years it has weathered economic storms; for that period it has outlived its own shortcomings, and the shortcomings of the people it set out to serve,” Ebenezer wrote in a column published Nov. 2, 1935. “On the threshold of its new era, it is natural that it pauses to look back on its past on the path it has tread, a path strewn with pitfalls, a path decorated with the glory of achievement; a path nonetheless dotted with journalistic wrecks. Much of the paper’s success must be measured in the friends it has made; much of its power can be measured in the enemies it has made. No man can get very far without creating a few enemies here and there. The man whom everyone loves is insincere. The Age‘s supporters flaunt its greatness; to many it is a beacon [of] light in this — their world of racial darkness.”

Celebrating Black History

30 Jan One of the added treats of finding these columns of my father has been taking note of the other writers and scholars with whom he shared space in the New York Age: Black conservative George Schuyler and his wife Josephine Schuyler; Arthur Schomburg, after whom the Schomburg Library for Research in Black Culture is named (Back then Schomburg, who was of Puerto Rican origin, went by “Arturo”);

One of the added treats of finding these columns of my father has been taking note of the other writers and scholars with whom he shared space in the New York Age: Black conservative George Schuyler and his wife Josephine Schuyler; Arthur Schomburg, after whom the Schomburg Library for Research in Black Culture is named (Back then Schomburg, who was of Puerto Rican origin, went by “Arturo”); and historian, author and educator Carter G. Woodson. Woodson founded Black History Week, which was scheduled for the second week of February, bracketed by the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. (According to Woodson, Douglass, who was born into slavery, did not know his actual birthday, but chose Valentine’s Day. Black History Week is, of course, the precursor of Black History Month, which we begin celebrating Tuesday. According to Wikipedia, “The expansion of Black History Week to Black History Month was first proposed by the leaders of the Black United Students at Kent State University [my graduate school alma mater] in February 1969. The first celebration of the Black History Month took place at Kent State one year later, in February 1970.”

and historian, author and educator Carter G. Woodson. Woodson founded Black History Week, which was scheduled for the second week of February, bracketed by the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. (According to Woodson, Douglass, who was born into slavery, did not know his actual birthday, but chose Valentine’s Day. Black History Week is, of course, the precursor of Black History Month, which we begin celebrating Tuesday. According to Wikipedia, “The expansion of Black History Week to Black History Month was first proposed by the leaders of the Black United Students at Kent State University [my graduate school alma mater] in February 1969. The first celebration of the Black History Month took place at Kent State one year later, in February 1970.”

Woodson also founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, an organization that was founded in 1915 and still exists today. He wrote more than a dozen books, including The Mis-Education of the Negro.

Woodson also founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, an organization that was founded in 1915 and still exists today. He wrote more than a dozen books, including The Mis-Education of the Negro.

Woodson argued that black people, particularly black youth, need to have a full picture of their history and historical contributions in order to develop the self worth it takes to pursue economic, political and social equality.

“If you teach the Negro that he has achieved as much good as others he will aspire to equality and justice without regard to race. Such an effort would upset the program of the Nordic in Africa and America. The present control of Negroes could not thereafter be maintained. The oppressor, then, must keep the Negro’s mind enslaved by inculcating a distorted conception of history,” Woodson wrote in a New York Age column published August 17, 1935.